Hi all! Welcome back to why our breathing pattern is important!

In Part 1 we talked about the muscles involved in breathing and how to test if your breathing pattern is “optimal.”

Today we will delve a bit into the why this matters!

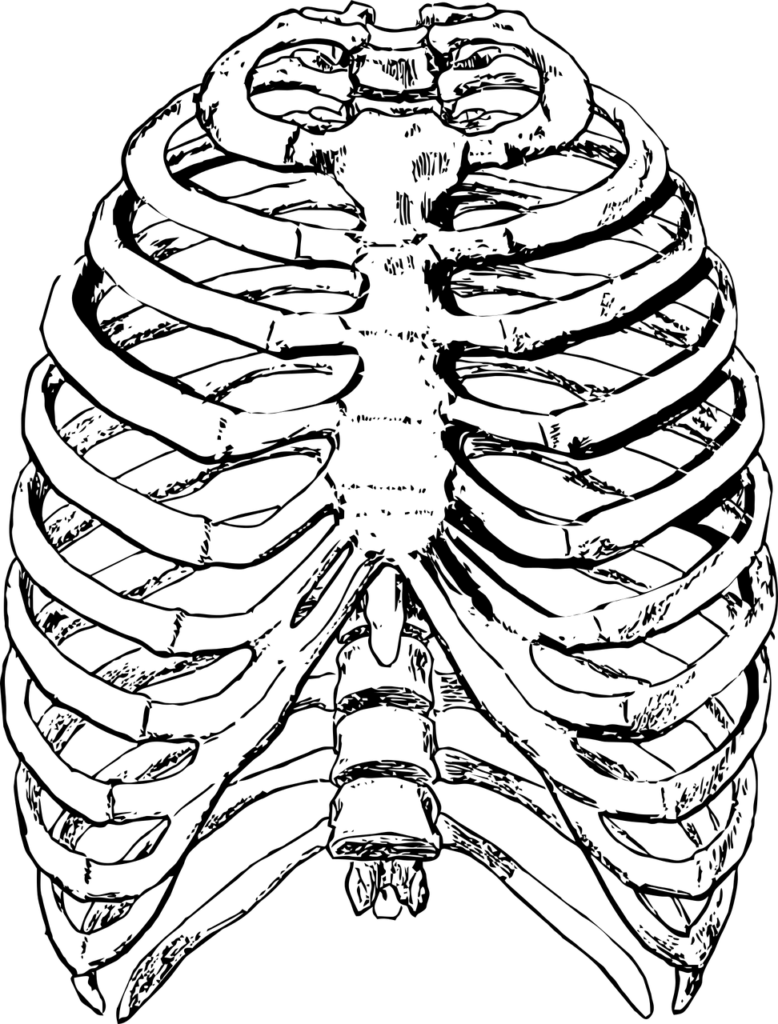

Role of breathing in ribcage expansion and joint mobility

If you remember… when we inhale, our intercostal and diaphragm muscles contract to spread out and elevate our ribcage to make room for the lunges to expand as they fill with air.

But stiffness in our joints between the spine and ribs can affect how well this expansion happens.

Alternatively, if our breathing pattern is not optimal, or not all of the muscles are engaging, we may get more expansion on one side than the other. The side that gets less expansion gradually gets stiffer.

As the ribcage attaches to the thoracic (upper and mid back) spine, its mobility also affects how our torso moves (e.g. turning our body to look over our shoulder).

As you can see, spine and ribcage mobility can both affect and be affected by our breathing!

Role of breathing in posture

In Part 1 we briefly talked about “accessory breathing muscles”, or muscles that are not active during regular breathing. Instead, they are activated during heavy exercise, a stressful situation, or an asthma attack, i.e. when breathing becomes hard work and more energy is needed!

These muscles also become active depending on our stress levels, our posture, or even when the major breathing muscles are not being optimally used.

When these accessory muscles are habitually used, our breathing pattern changes so that we become more “apical” breathers. This means that most of the movement happening is through our chest and shoulders.

However, most of the movement should be happening from the expansion of the ribcage!

These accessory muscles then become overactive and tight, while our diaphragm is underused, and our ribcage becomes stiffer.

This leads to, and is reinforced by, a more slouched posture:

- Head and neck positioned more forward

- Greater curve (or “hump”) in the upper and mid back

- More rounded shoulders and tighter pec muscles

Role of breathing in stress and anxiety

A lot of people carry stress in their neck and shoulders. This is also reinforced by a lot of us sitting in front of a computer all day. As we sit for prolonged periods of time, we naturally crane the neck forward toward the screen, round the shoulders and upper back, and slouch through the lower back.

Our stress and anxiety can affect how much muscle tension we carry. Have you ever noticed that when you are cold, you hike your shoulders up and tighten the neck?

What about when you are stressed, anxious, or even just overly focused on your work? Do you hike up your shoulders, or clench your jaw?

Interestingly, our respiratory rate (our breathing) can influence our nervous system and therefore, our muscle tension.

For example, if we are in a more stressed state (fight, flight, or freeze response), if we consciously slow down our breathing and lengthen our exhales, we can switch over to a more relaxed state (rest and digest state).

There are known as the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system… When we are in an amped up state (sympathetic response), we carry more tension. When we are in a relaxed state (parasympathetic response), our muscles are also more relaxed.

You can try this as a stress management technique!

Every time you find yourself stressed or anxious, take a moment to close your eyes, consciously relax your shoulders, or anywhere else you feel you are tense.

Then, take five deep breaths, making the exhale twice as long as the inhale.

e.g. Breathe in to the count of three. Exhale to the count of six.

Another breathing technique for when feeling anxious is alternate nose breathing:

- Exhale through the nostrils

- Then, close the right nostril with your right thumb and inhale slowly through the left nostril

- Then, close the left nostril with the right ring and pinky fingers, and slowly exhale through the right nostril

- Still covering the left nostril, slowly inhale through the right nostril

- Then, close the right nostril again with your thumb and slowly exhale through the left nostril

- Repeat either nine rounds, or for about 5 minutes

- End on a left nostril exhale

Role of breathing in low back pain

If your ribcage and spine are stiff, you may experience some upper and/or mid back pain.

That stiffness may be also contribute to low back pain…

Let’s take the psoas muscle as an example. The psoas flexes your hip, but can also function as either a spine stabilizer or a spine mover. In others words, it affects our back stability and mobility.

That’s because the psoas attaches to both the lumbar spine and to our hip bone. However, it also attaches to the diaphragm through the fascia! Therefore, it has the potential to be affected by our breathing.

If we are chest or belly breathers, our ribcage and low back do not expand much with our breath. This is the path of least resistance for the breath.

If our psoas is tight, it reinforces a suboptimal breathing pattern because we are going to continue breathing through that path of least resistance into either the chest or the belly.

But when we focus our breathing into our sides and back, we can help relax some tight muscles, like the psoas, that can be contributing to low back pain and/or tightness.

Here is an exercise you can try to do this:

Start by lying on your side. Curl into the fetal position so that we are opening up the back and blocking the abdominals. You can even hug a pillow to brace the abdominals.

Now, take a few regular (or slightly deeper) slow breaths. Every time you inhale, think about forcing that breath into the back (upper and/or lower), feeling it slightly expand out.

Then, as you exhale, feel the the expansion come back in.

You can even place your top hand on your lower ribcage, pushing the hand away on inhale, and pushing the hand down into the ribcage on exhale.

Role of breathing in core strength

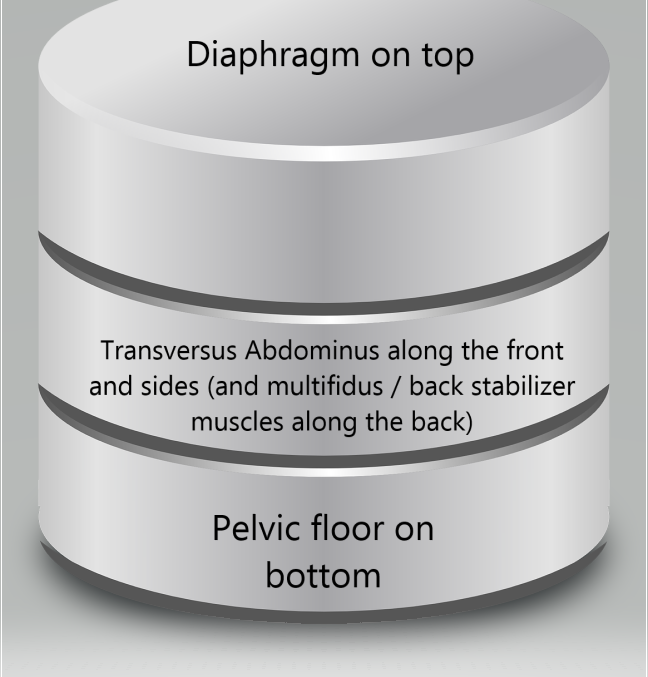

The diaphragm attaches to the ribs, sternum, and lumbar spine. As such, it is both a respiratory muscle and a postural stabilizer.

Imagine the core units surrounding the abdominal cavity as a container:

- Transversus abdominus muscle at the front and sides

- Back stabilizer muscles like the multifidus and erector spinae at the back

- The diaphragm at the top

- The pelvic floor muscles at the bottom

As you can see, the diaphragm is part of our core unit! Therefore, how well it is functioning can impact the rest of our core muscles.

Our breathing pattern is foundational. In fact, more and more research is showing that the first step to core strength, stability, and overall function is diaphragmatic breathing.

More than that, we want that diaphragmatic breathing to expand our ribcage from all sides, rather than just focusing on pushing out the belly with the inhale. In others words, we want a 360 degree expansion with each inhale!

Role of breathing in diastasis recti

If you remember from Part 1, as you inhale, the diaphragm contracts and moves down to allow for the lungs to fill with air.

This causes the pressure to go into the abdominal cavity (see the cylinder diagram above!).

Pressure will follow the path of least resistance, which means it will usually go to the belly and distend some of that front fascia (i.e. the abdominal diastasis).

If we carry a lot of tension in our abs and tend to brace there, breathing into the fascia is a good thing. We can help relax and stretch that fascia.

But if we have some weakness there (e.g. postpartum), then belly breathing reinforces stiffness/tightness in the back and weakness in the abdominals because the breath is constantly following the path of least resistance, and pushing into the weak abdominals.

This can then reinforce the diastasis recti, rather than help heal it.

Therefore, focusing the breath into tighter areas, like the back, is preferable.

Role of breathing in pelvic floor

As shown in the cylinder diagram above, our pelvic floor muscles form the base of our core. This means that your pelvic floor is also a spine stabilizer. (In fact, sometimes pelvic pain can refer to the back!)

When we are belly breathers, we often breathe through the upper abdominals. However, women postpartum often have more weakness in the lower abdominals, which means that’s where the path of least resistance will be.

This puts more pressure down into the lower abdomen and pelvic floor.

As a result, women who close their diastasis recti more quickly postpartum often have a greater risk of prolapse!

To prevent the pressure system from placing too much strain on the pelvic floor, we want to reduce the upper abdominal tension, strengthen the lower abdominals, and overall encourage a breathing pattern that expands on all sides (front, sides, and back)! And eventually, even breathing down into the pelvic floor!

If you are having back pain, or recovering from a diastasis recti, and would like to learn more about what you can do (including the role of breathing for core strength and general mobility), let us know! We offer both in-person and Telehealth Physiotherapy services 😊